Today, the sixth of eight appointments with the critic reflection by Antonello Tolve who retraces the complex relationship between art, technology and nature, by surveying a number of artworks connected to the relation man/environment, from Land Art to Transgenetic Art to Bio Activism.

Landscape-oriented, but from a more eco-friendly position – a position inextricably binding together the subject of the artwork with ecology, as Cesarina Siddi rightly points out[1] – are the works that the pioneers of EcoArt Movement, Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, have been carrying out since 1969, realizing trans-conceptual scenarios connected to landscape, to the preservation of botanic ecosystems against its threating agents.[2] The various projects comprised in their Future Garden, produced in Bad Zwesten and Bonn between 1996 and 2000, display an exemplary and surprising behavior where nature is taken care of, an act of caring that involves museums and art galleries, as well as public institutions, through an expressive territory extending, thanks to public debates, well beyond art circles: “Our work begins when we perceive an anomaly in the environment that is the result of opposing beliefs or contradictory metaphors” suggest the Harrisons. “Moments when reality no longer appears seamless and the cost of belief has become outrageous offer the opportunity to create new spaces – first in the mind and thereafter in everyday life”[3]. Environmental and ecological artists, the Harrisons span across different languages and being historians, teachers, college professors, diplomats, ecologists, detectives, art dealers offer a wide array of concrete and metaphorical works as food for thought for art aficionados and the general international public as well.

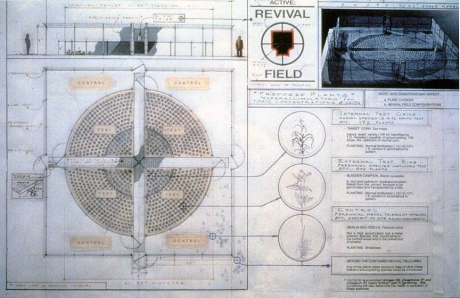

In relation to an artwork, the site of its creation can be dominant, as in Henry Moore, specific as in Richard Serra, or adjusted as in Mark Du Suvero, who works in an atelier. The site has heavily influenced and determined the operation of reclamation made in St. Paul, Minnesota, by Mel Chin, who is ideologically akin to Harrison. With Revival Field (1991), he created an organic device – a “sculpt a site’s ecology”, to be more precise – that, also thanks to advanced technologies, can decontaminate a place from the heavy concentration of metal in the soil.

Born from a field-experiment carried out with hyperaccumulating plants (applied for the extraction of heavy metals from the polluted soil), this project – realized with the advice of agronomist Rufus L. Cheney at the US Department of Agriculture – confirms that nature can be healed through its own instruments and internal procedures. According to the results yielded during the verification phase, the biomass samples taken from the site confirm the surprising improvements of the reclaimed area, and therefore “the potential of Green Remediation as an on-site, low-tech alternative to current costly and unsatisfactory remediation method”. Despite “soil conditions adverse to metal uptake, a variety of Thlaspi, the test plant with the highest capacity for hyperaccumulation, was found to have significant concentration of cadmium in its leaves and stems”[4].

Similar to an orchard or a circular garden or an oasis in the desert[5], Revival Field, which, together with CLI-mate (2008)[6], is Mel Chin’s most complex ecologic creation, is an enlarged work of environmental art. As it discusses environmental sustainability, it expands the area of the artist’s intervention and presents itself with an explicit ecological dimension. For him, the artist’s gesture is an emergency action, a project of ecological restoration going beyond art and emphasizing an aesthetic will where value surpasses form and turns itself into a physical action taking place on and within the landscape.

[vimeo id=”10874104″ width=”620″ height=”360″]

…to be continued…

[1] C. Siddi, “Arte e paesaggio. 5 (s)punti di riflessione”. Architettura & Città. Società dentità e Trasformazione. Milan: Di Baio Editore, 2006, 106.

[2] On the work of this artistic duo, see at least their own theoretical contribution contained in H. Mayer Harrison, N. Harrison, “Shifting Positions Toward the Earth: Art and Environmental Awareness”. Leonardo, vol. 26, no. 5, 1993. 371-377; Iid., “Le Cycle du Lagoon”. Manifeste Pour l’Environnement au XXIe Siècle, edited by B. Laville and J. Leenhardt. Paris: Actes Sud, 1996. 177-205; Iid., “Knotted Ropes, Rings, Lattices and Lace: Retrofitting Biodiversity into the Cultural Landscape”. Biodiversity. A Challenge for Development, Research and Policy, by W. Barthlott and M. Winiger. Berlin | Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1998. 13-31; Iid., “Shifting Positions Toward the Earth: Art and Environmental Awareness”. Women, Art & Technology, edited by J. Malloy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003. 160-179 (all items downloadable at theharrisonstudio.net).

[3] H. Mayer Harrison, N. Harrison. Home, at theharrisonstudio.net, accessed on 20 Aug,, 2015, at 8.27 pm.

[4] M. Chin, Revival Field (concept), at melchin.org, accessed on 20 Aug., 2015 at 11.13 pm.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For an overview of the artist’s works more strictly connected to an environmental philosophy, see under the section “Ecology” of his website.