Prof. Massimo Bergamasco is an expert in mechanics applied to robots, founder of the PERCRO Perceptual Robotics Laboratory at the Scuola Superiore S. Anna in Pisa and much more. His interests range from wearable exoskeletons, to haptic interfaces, to the development of virtual environments and augmented reality, a transversal view that has been able to look ‘beyond’ ahead of time. In a conversation via skype (April 2021), Bergamasco has projected us into the ecology of the future where drones, robots and synthetic humans, will be integral part of the ecosystem.

Elena Giulia Rossi: You have always been involved in robot mechanics, wearable exoskeleton robots and haptic interfaces, but also in the development of virtual environments and augmented reality. What role will these fields have in the “ecology of the future”?

Massimo Bergamasco: These fields will represent an integral part of our future ecosystem. We should get used to it. Man will be required to work in professions other than those of today. Some time ago it was unimaginable, for example, that there would now be technicians working on virtual environments. Think of the Internet. Twenty years ago, its use and social impact could not have been predicted. Especially today it would be unthinkable to do without it.

We must not make the mistake of considering the future ecosystem on the basis of what exists today. We don’t yet know what jobs, or even objects and machines, will look like in the future. We can’t yet predict which inventions will generate new paradigms, including those related to human behaviour at social level.

Humans will be forced to interact as much with robotic systems as with digital entities, such as virtual humans. This will happen everywhere, not just in laboratories. Society will also change based on how people interact with these machines, these artificial entities. The way people interact with each other will also change as a result.

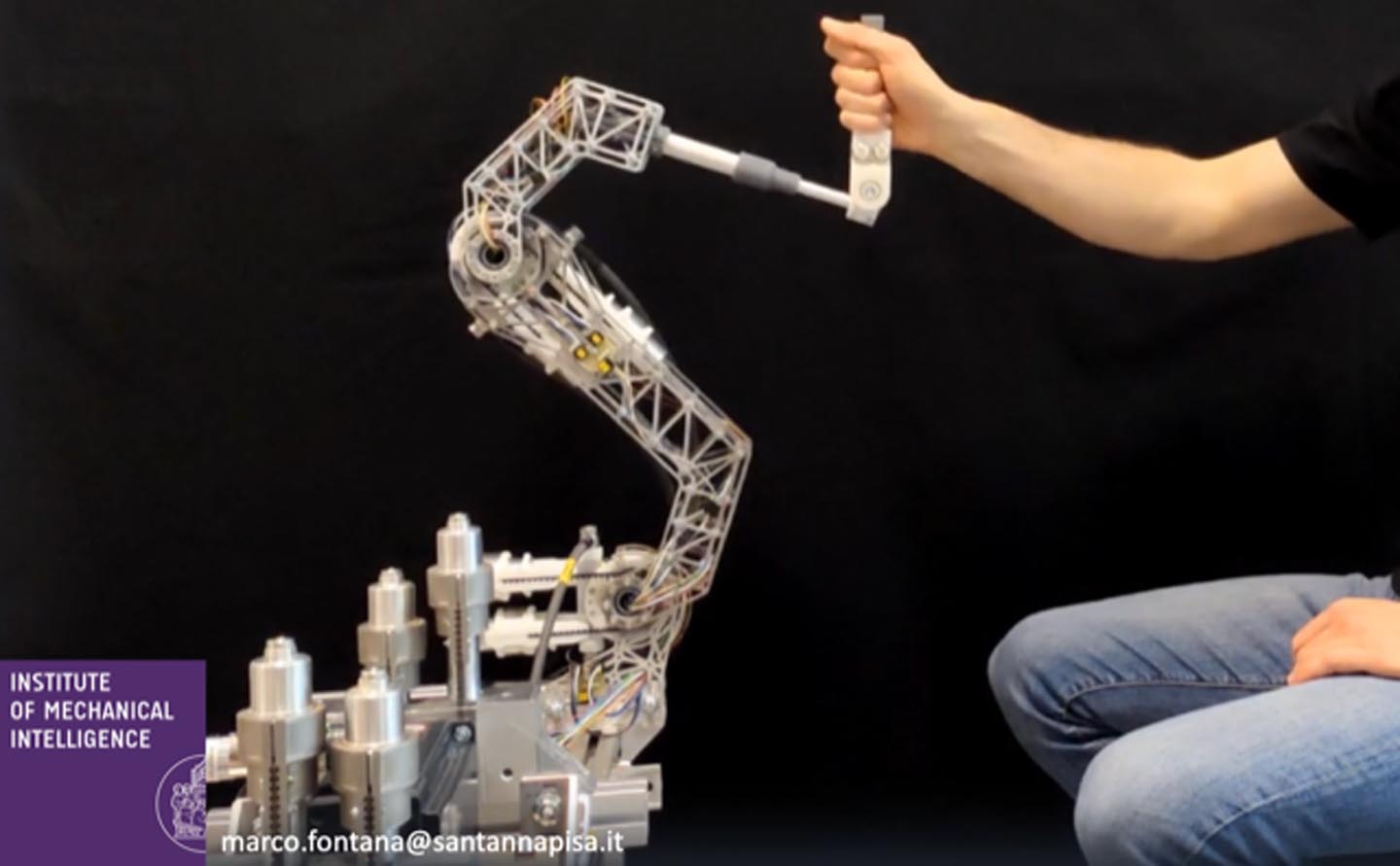

We have mentioned our research into exoskeletons, a field in which you are pioneers both in Italy and worldwide, where they are mainly employed in the medical field (particularly in rehabilitation). Can you tell us exactly what they are and what it means to pursue research in this area?

An exoskeleton is a robotic system that humans wear, for example, to help them in their movements. The research focuses on the study of materials that can be as flexible and adherent to the body as possible, that can support the body’s movements and amplify its capacity for strength or resistance.

A current area of research concerns the development of appropriate power generating systems, hopefully increasingly lighter in terms of weight and volume, in order to make exoskeleton machines more and more efficient.

Today’s electric vehicles, for example, weigh more than those with internal combustion engines. This is due to the presence of batteries. This research, focused on the weight and autonomy of actuation and energy systems, will also be directed at robotics. There will come a point when wearing an exoskeleton will be similar to wearing a tight-fitting body suit.

In what fields can robotics, in particular exoskeletons, be used in agriculture?

I remember that, when I was studying for my PhD, one way in which robotics was used in agriculture was by building mobile robots that could go and pick fruit, the video camera recognising objects according to their colour when compared with the colour of the leaves. At the time, I remember a great deal of effort was put into studying a robot’s hand, controlling the shape and how much pressure to be applied to the fruit at harvest time, so as not to damage it. Now these application systems have made incredible progress.

For either a field or vineyard, the design must be made on the basis of the machines that are then used in them. This will become increasingly important with the introduction of robotic systems. A robot needs to know where it is in order to move. It’s given a two- or three-dimensional model of the environment and a motion-planning strategy enabling it to follow certain trajectories. So it must know the environment. It can also know it in real time, as Boston Dynamics’ mini spot does today using a unique application for exploring mines more than a thousand metres underground where the robot can collect samples of materials.

Exoskeletons can also be used in forests to lift heavy loads. A logger might use an exoskeleton to lift a log.

Even in this case, for the development of research, it’s important to study the materials, reduce the volume of the structure, making it light and flexible so that it can tackle a variety of obstacles in the forest in a much simpler way. In the future it’s possible that the woodcutter may be replaced by humanoid robots or machines that will saw the wood in other ways. I’ve seen robots hooked around the trunk employing a vertical movement that can cut through all the branches. This is quite recent. Before, they couldn’t even have been imagined.

Some time ago you told me that there is a widespread use of drones in traditional agriculture…

In fact, drones are widely used in so-called “precision agriculture”. When a clearing operation is required or disease-fighting substances need to be applied to certain types of plants, a drone can distribute these very quickly and on time. Drones can perform very accurate monitoring operations. For example, in a vineyard, the drone can acquire information about the state of the grapes and help make important decisions if the farmer can’t physically visit the site. The same applies to any other type of cultivation.

For some time now, your laboratory has also been conducting cutting-edge research into virtual humans. Can you tell us what this is about? What role will it play in the future?

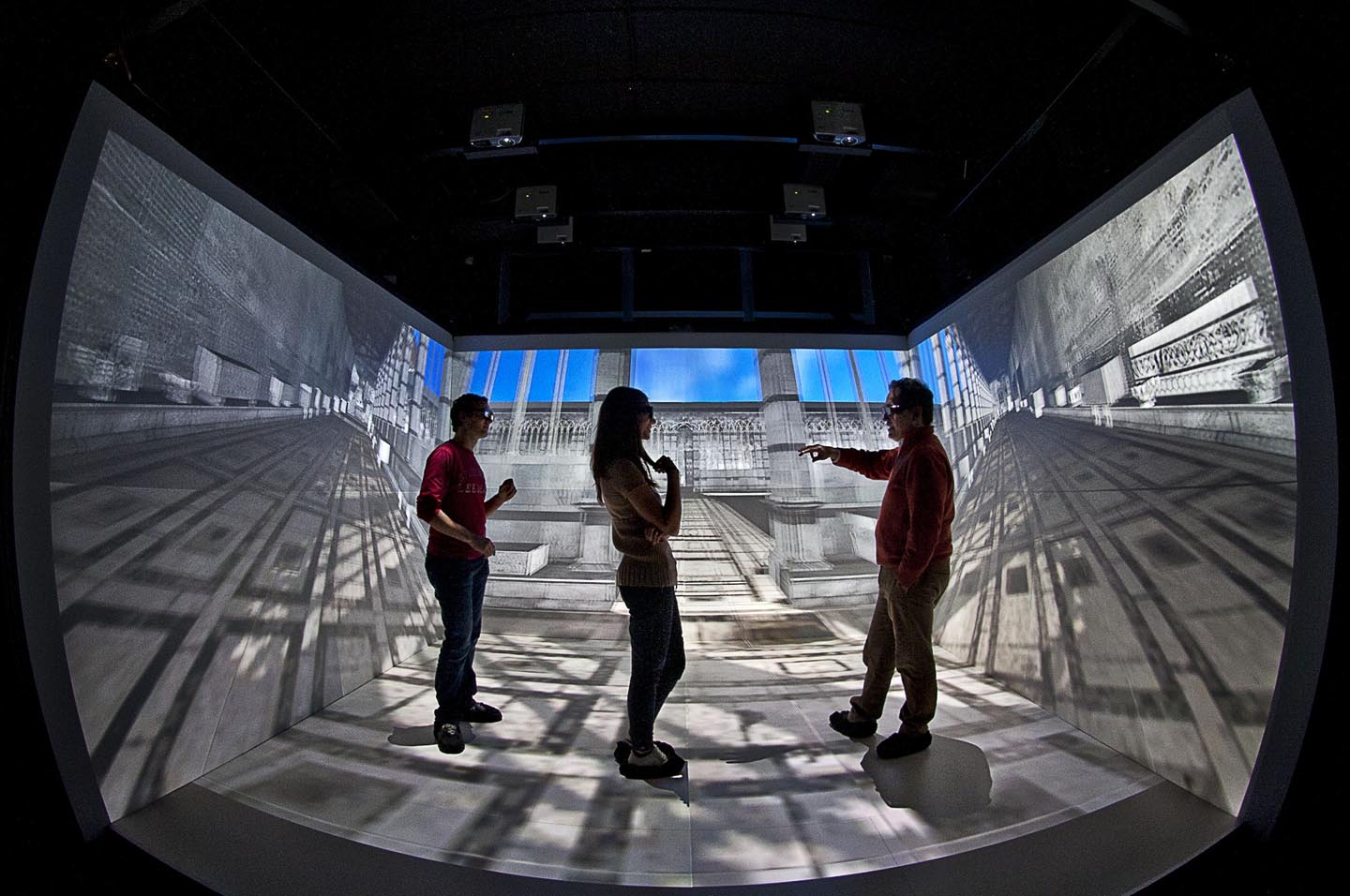

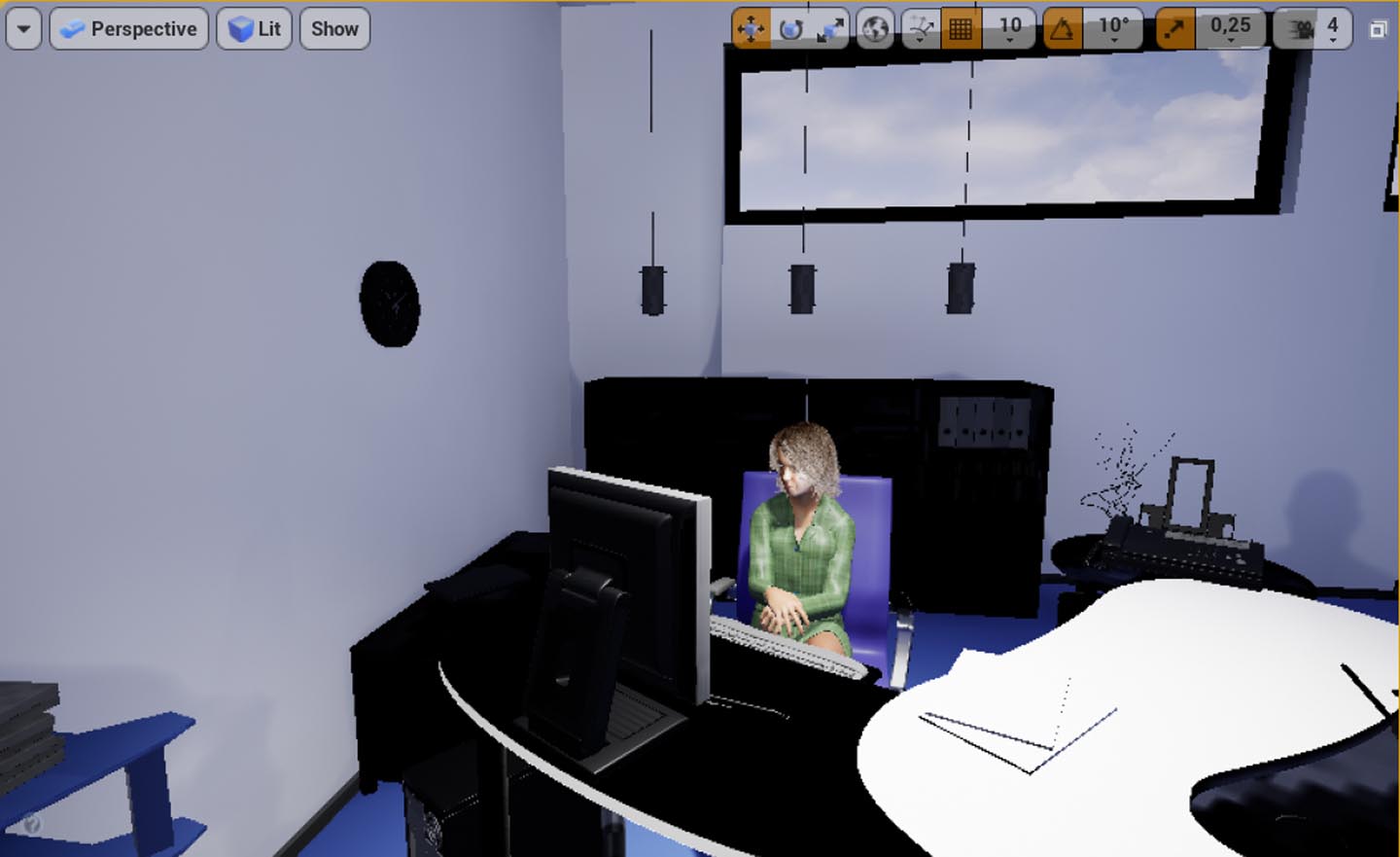

A virtual human is a synthetic entity generated and controlled by a computer. The aim is to ensure that this control is not managed by humans but by the artificial entity itself. It’s a similar process to making an autonomous robot. In future, we will have to think of autonomous virtual agents capable of learning the tasks they have to perform, managing their own movements and acquiring, through perceptive systems, knowledge about the environment so they can make decisions. At a higher level, in order for a virtual human to be able to interact with biological humans, work must also be done on the artificial entity at the emotional level.

How and by whom are these virtual humans educated?

Currently, virtual humans are educated by humans. At the moment, they’re not yet entities with the ability to understand what’s happening in the virtual and physical world. They know what humans tell them and interact with other virtual humans. In order to interact with humans, the virtual human must acquire a perception of reality through cameras and sensors. It can also communicate with humans through natural language.

The aim is for virtual humans to acquire enough knowledge to use the experience they have gained during the training phase. They’re currently controlled on the basis of certain commands and reactions programmed by humans. In future, they will be equal to a machine that understands what’s happening, compares it with billions of data stored in the system’s memory and can therefore understand whether something is done well or not. Today these aspects of learning are extremely important for the development of autonomous systems. The machine is able to understand what it sees. How does a deep-learning algorithm recognise a dog? It’s shown billions of pictures of dogs and other animals. In the end, it recognises the dog on different levels of neural networks which, starting from the details, are progressively able to build up the recognition of parts, then larger sets up to the general shape of the animal.

When confronted with the image of a dog, a horse and a coyote, the algorithm is able to say with a certain degree of certainty which one corresponds to a dog. The training phase is very important.

In which fields are virtual humans used?

At the moment, they’re widely used in medicine, particularly during surgical training. In an operating theatre scenario, along with a mannequin, there are screens from which virtual humans watch students training in surgery. They capture the students’ movements and decisions through cameras and can guide and correct them when performing certain operations by comparing billions of cases recorded in their memory.

Virtual humans are also virtual museum guides. In one of the most recent applications they look extremely realistic, taking on the appearance of anchor men. Sometimes it’s very difficult to distinguish them from video representations of biological humans.

How should humans position themselves so that these new realities can become allies rather than antagonists?

In my opinion, we also need to partially demythologise the role of future technologies. A lot of progress will certainly be made, but it will take a long, long time before machines manage to surpass or even replace humans, as some are predicting. This is my point of view.

There are currently engineering technologists par excellence who claim that in forty to fifty years they will enable machines to achieve a higher intelligence. There are those who argue the opposite and say it will take 500 to 1000 years. In my opinion, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. You don’t have to be afraid, but you don’t have to be so enthusiastic about tech either.

Much has been said about the fact, which is true, that the computational capacities of digital systems have increased tremendously (it was claimed that the computational capacity of systems doubled every eighteen months). Since I started in the early 1980s things have moved on a lot. I now have in my pocket, in my smartphone, far more computing power than the machines that once cost hundreds of millions of lire. It’s clear that we gradually adapt to new technologies. It will be a long time before we get to something that is totally autonomous.

The physics of systems cannot go on forever. We now expect that these systems will be able to perform operations with even greater intelligence than humans, but we don’t know for sure. These are only our projections. My position at the moment is to accept technological development, the development of autonomous virtual human robots. Then we’ll see how we will behave, but first we have to get there, and I think it will take a long time unless there are technological changes that we can’t foresee at the moment. Certainly, studying these artificial systems is important and allows us to get to know ourselves better. If we could understand all the cognitive mechanisms and one day replicate them in machines, we would begin to understand how we function.

How will research have to change to adapt to the coming ecosystem where real and virtual humans and robots will have to coexist?

Research will be increasingly collaborative and will include social and political aspects. Policy-makers will have to be people who understand technology, where and how it can be applied.

I’m very much counting on multidisciplinary studies in the future. Even philosophy should be taught to technologists. One has to understand why one does things, not only on an emotional level but also ontologically. Many researchers conduct research often with a lack of motivation, or with motives which are limited or constrained. They fail to integrate their research into a global framework or into one which helps others. These things are personal rather than social.

Massimo Bergamasco is Full Professor of “Mechanics Applied to Machines ”at the Scuola Superiore S. Anna in Pisa, where he held the position Director of the Institute of Communication, Information and Perception Technologies (TeCIP) from 2016 to 2019. In 1991 he founded the Perceptive Robotics laboratory PERCRO, which carries out research in the areas of design and development of wearable robots, haptic interfaces and development of Virtual Environments and Augmented Reality. He has been scientific coordinator of numerous national and international projects. He is author of a large number of scientific publications. Since 2018, he is President of Centro di Competenza ARTES 4.0, coordinated by the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies.

The interview to Massimo Bergamasco is part of GAME OVER.Loading, a project aimed at researching and studying new “cultural entities”, people, objects or research from different disciplines (physics, bio-robotics, AI, agriculture and medicine) and transporting them into the art world. This is a research project, but also a gesture that goes beyond simple interdisciplinary dialogue, becoming quite radical: a real “transplanting” of research areas aimed at preparing future c(o)ulture, where “creativity” equals “invention” and “invention” equals contributing to a transformation. A spark, a sign of a genetic mutation, a change of direction, a short circuit. A different energy that is also marks a change which is taking place and could constitute new lifeblood for the Culture system. This first phase is an investigative one aimed at visionaries, hybrid thinkers from various fields, including those from the cultural sector, who can express their views on current needs, each in relation to their own disciplinary field while generally respecting culture and society at large. Project team: Anita Calà Founder and Artistic Director of VILLAM | Elena Giulia Rossi, Editorial Director of Arshake | Giulia Pilieci: VILLAM Project Assistant and Press Office; Chiara Bertini: Curator, Coordinator of cultural projects and collaborator of GAME OVER – Future C(o)ulture | Valeria Coratella Project Assistant of GAME OVER – Future C(o)ulture.

All previous interviews and interventions: Interview to Primavera De Filippi by Elena Giulia Rossi (Arshake, January 21, 2021); interview by Azzurra Immediato to Leonardo Jaumann (Arshake, 28.01.2021); interview to Valentino Catricalà by Anita Calà and Elena Giulia Rossi (Arshake, 04.02.2021); multiple interview Stefano Cagol to Antonio Lampis, Sarah Rigotti, Tobias Rehberger, Michele Lanzinger, Stefano Cagol (Arshake, 11.02.2021); interview to Amerigo Mariotti by Azzurra Immediato (Arshake, 25.02.2021);Andrea Concas’s video intervention (Arshake, 18.02.2021); Interview to Peter Greenway by Stefano Cagol (Arshake, 04.03.2021), Intervento di Giulio Alvigini, Bye Bye Boomer, Game Over Art World (Arshake, 11.03.2021); Interview to Ken Goldberg by Elena Giulia Rossi (Arshake, 18.03.2021); Intervention of Eduardo Rossi, invited by Chiara Bertini (Arshake, 25.03.2021); interview to Anuar Arebi by Azzurra Immediato (Arshake, 31.03.2021); Interview to Giovanni Gardinale by Valeria Coratella (Arshake, 15.04.2021);Interview to Luca Gamberini (Arshake, 22.04.2021;Interview to Lorenzo Piombo (Arshake, 29.04.2021);Interview to Art is Open Source by Anita Calà (Arshake, 06.05.2021); Interview to Giuseppe Mariani by Azzurra Immediato (Arshake, 13.05.2021);interview by Chiara Bertini to Nicola Poccia (Arshake, 27.05.2021);interview to Francesca Disconzi and Federico Palumbo (Osservatorio Futura), Arshake, 03.06.2021; interview to Pier Luigi Capucci di Elena Giulia Rossi (Arshake, 10.06.2021).